The History and the Melodic and Rhythmic Modes in Irish Music

- History

- Melodic Modes

- Rhythmic Modes

- Lilting, aka Mouth Music and Puirt a Beul.

- Sean-Nós singing

- Airs

- Timeline

- Irish sheet music online.

- References

Short History of Irish Music

Irish bagpipes (Uilleann pipes) are the oldest musical instrument (other than voice) in the Irish tradition, leading to piping ornamentation becoming an important part of the Irish music produced by all subsequent instrument. "The pipes are a peculiar musical instrument, because they emit a continuous tone; therefore, the piper must use ornamentation to make the melody stand out. This generates a rich and very specific system of ornaments: cuts, taps, rolls, cranns, etc. The piping ornaments were adapted to the other traditional instruments and more ornaments were added, and this ornamentation is a very important part of the Irish music sound."— Tricia Hutton

Plucked and bowed lyres and harps were common by the time Gerald of Wales (Girald Cambrensis) did his tour of Ireland in the 12th century. He found little to admire about the Irish natives other than their music. "The only thing to which I find that this people apply a commendable industry is playing upon musical instruments , in which they are incomparably more skilful than any other nation I have ever seen. For their modulation on these instruments, unlike that of the Britons to which I am accustomed, is not slow and harsh, but lively and rapid, while the harmony is both sweet and gay... They enter into a movement, and conclude it in so delicate a manner, and play the little notes so sportively under the blunter sounds of the base strings, enlivening with wanton levity, or communicating a deeper internal sensation of pleasure, so that the perfection of their art appears in the concealment of it."

Dance music figures largely in the folk music of Ireland. Before the advent of the baroque violin, (imported to Ireland in the late seventeenth century and being made in Ireland in the early eighteen century) the harp, pipes and flutes were the backbone instruments of Irish music. By the end of the eighteenth century, the fiddle was the instrument of choice for music for dancing, especially in North Ireland, influenced by the Scottish enthusiasm for fiddle music and reels.

"The baroque fiddle...may have been introduced from England in the second half of the seventeenth century, although the earliest evidence for such importation is not found until the early 1720s. Fiddles were being made in Dublin later in the same decade and used for the playing of Irish music... The great popularity of the fiddle in Scotland in the late eighteenth century, and a burst of reel composition associated with it, had a particular influence in the North of Ireland, and the fiddle has been especially strong there... It seems to have been the most popular instrument for the playing of Irish traditional music in the nineteenth century, and it possibly has been in the twentieth... Since the 1920s the fiddle has had a particular influence on the entire instrumental music tradition through the commercial recordings especially of three virtuoso fiddle players from Sligo: Michael Coleman, James Morrison, and Paddy Killoran, who made their local repertory and style nationally popular. " —Taisce cheol nUchais Eireann.

Ireland's adversarial relationship with England had its influence on Irish music. The well-known order from Queen Elizabeth to hang harpers wherever found and to destroy their instruments is probably apocryphal, but musicians were often suspected of spying and of rebellion with their music. What is not apocryphal is that laws were passed making it illegal for the Irish to speak their language, to own land or get an education. The lands and titles stripped from Irish aristocracy were bestowed on loyal subjects who, as absentee landlords, cut a dashing figure in London with the rents collected by land agents from increasingly impoverished Irish farmers. There was very little in the way of a local aristocracy or a middle class to support musicians; dancing masters, with a small fiddle in their pocket, traveled around Ireland hoping for a chance to earn a bit of money with dance lessons.

Lilting, or the art of chanting nonsense syllables in strict rhythm to a tune, evolved to provide dance music without musicians for many a house party in both Ireland and Scotland.

The Potato Famines of the mid-nineteenth century forced a million and a half Irish people to America, and with them came the love of their own music and a chance for the musicians among them to find work in the numerous traveling shows that brought the music to home-sick Irish Americans.

In the 1920s, the American recording industry exploded. Ethnic music markets provided ready-made customers anxious to buy, and the Irish market was huge. The recordings of Michael Coleman, an exemplary Sligo-style fiddler, became very influential. His recordings exerted a strong influence on fiddlers in America and in Ireland, and the local styles in Ireland, the result of centuries of rural isolation, began to change under the influence of American records.

Interest in traditional music waned after WWII on both sides of the Atlantic, but was revived in the 1960s with the general interest in folkloric traditions, and has continued to grow... sometimes in the direction of fusion with jazz, rock or other genres, and sometimes back to 'the roots.'

One reads about Regional Fiddle Styles. They still exist, although the original hundreds of styles have shrunk down to a handful, thanks to the availability of music media and transportation devices that eliminate isolation. In short, the closer to Scotland, the faster the song and the more aggressive the bowing. The southern-most counties are known for non-aggressive slides and polkas. My personal favorite is the Clare style, a bit south of the middle and bordered by the Atlantic Ocean, a style which makes no apology for being both a bit slower and evocative... although when I went into a record shop in Doolin and asked for some Clare style fiddle CDs, I was asked if I wanted West or East Clare and informed that Martin Hayes exemplified East Clare style - but then, everything is East of Doolin. I have also developed a taste for Sligo style, thanks to Kevin Burke, whose impeccable timing and Zen-Master approach to tune and ornaments won my heart decades ago. Sligo is described as fast and bouncy, but Kevin Burke has a way of savoring every note in a fast tune... as I said, a Zen Master of Irish fiddle.

Melodic Modes for the Irish Fiddler

"Irish tunes are not constructed within the diatonic (major and minor) idiom of classical music but in the older system of modes. It is not necessary to understand the theory of modes to play the tunes... But four modes are used in Irish music, two that sound 'major,' two that sound 'minor.' They are called the Ionian, Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian modes and correspond to the scales you'd get if you played only the white notes of a piano, starting on C, G, D and A respectively." — Peter CooperThe improvisational nature of Irish music is as important as the modal underpinnings. Improvisation is often accomplished with a simple grace note, a slurred bow instead of two short bows, or coming into the start of a phrase up bow instead of down. The essence of Irish music performance is to keep it honest and to keep it asymmetrical so that the pulse of the music rolls like a wheel. After you know the skeleton melody of a tune thoroughly enough to sing it, don't repeat a phrase using the same combination of ornaments and bowing twice in a row. Change it up a little.

"Once the structure of a tune is firmly in a fiddler's head, he can vary the ornamentation, substitute one phrase for another, or even create elaborate variations, all with the greatest of ease and possibly without even realizing. Unlike with classical music, where there is one right way and a million wrong ways to play a tune, a traditional melody in the hands of a skilled fiddler is a living, breathing thing that belongs as much to the performer as it does to the composer, if such a single person ever existed." —Chris Haigh

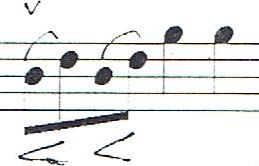

Ornaments are executed with the left hand on the fingerboard. Kevin Burke teaches that an ornament, although technically a series of notes, is not melodic; it is an interruption of the vibration of the string. Play the main note clearly. Play the ornament note(s) quickly and lightly, and do not worry about intonation. The interruption of the vibration, not a new vibration, is what you are aiming for.

Here is a short-and-sweet reference table. Like everything else in Irish fiddling, these are not hard and fast. For instance, some folks use a third finger instead of a second when ornamenting a note on the first finger. (Right - say that three times fast.)

| Finger | Cut | Cut: Double |

Roll: Up-down |

Roll: Down-up |

4-note Short roll |

| Open (CRAN) | 3 0 | 0 1 0 | 0 1 3 1 0 | 1 3 1 0 | |

| 1st | 3 1 | 1 2 1 | 1 3 1 0 1 | 0 3 1 0 1 | 3 1 0 1 |

| 2nd | 3 2 | 2 3 2 | *2 3 2 1 2 | 1 3 2 1 2 | 3 2 1 2 |

| 3rd | 4 3 | 3 4 3 | *3 4 3 2 3 | 2 4 3 2 3 | 4 3 2 3 |

* The interval between the roll's 3rd and 4th note is a half-step, no matter what the key signature is.

| |||||

—Adapted from Mick Connally's diagram of roll fingering.

Cuts

Cuts are grace notes; a little flick on a higher note. These are often used in between notes of the same pitch. Remember: this is an interruption, not a part of the melody. Flick it and do NOT change bowing or strings!Do not delay the regular note for the grace note: The regular note is on the beat, the grace note precedes..

Double Cuts

Double cuts are, surprise! pairs of grace notes, often used to add depth to a step-wise progression up or down the scale. The first note in the cut is the same as the main note; the second note in the cut is the note above. Then back to the main note. As with the single cut, do not delay the regular note for the grace notes; the grace notes precede.Rolls

Remember: Irish ornaments are interruptions, not music. Kevin Burke says to make rolls RATTLE. Do not divide the beats evenly; the roll is a series of interruptions to one note (neutral). Neutral; Up, back to neutral, down, back to neutral, with the grace notes above and below crowded towards the center of the roll. Keep your fingers light, and exert no more pressure than necessary to stop the vibration. A touch, not a touch-down.- A roll, AKA a long roll, has the duration of a dotted quarter note.

- A short role has the duration of one quarter note. Some squeeze the five notes of the long roll into a short role; others use four notes.

Slides

Start slides a half tone lower than the destination note and slide up. This ornament is very emphatic: Keep bow soft at start of slide and do not over-useDouble Stops

Irish music is not bluegrass. Use double stops with discretion. Try them on the even beats instead of the odd. Keep them light by glancing towards the secondary string.Triplets

By now you have probably gotten the general idea: symmetry is not the ideal. In the case of triplets: first two fast, third note slower. Like the cuts, do not try to make them musical; make them rattle or stutter. Kevin Burke describes these triplets a shake of the bow followed by a longer note, closer to a group of two sixteenth notes followed by an eighth note.Rhythmic Modes for the Irish Fiddler

Since most of instrumental Irish music is dance music, understanding the dance rhythms is key. (The airs are a notable exception: they are not dance music and have no distinct rhythm; all the components of the song are adapted to serve the feeling behind the music.)Improvisation can be both melodic and rhythmic, and kinetic bowing is an important part of improvisation. It can be as simple as starting one phrase down bow and the next up bow. Accenting into the end of a bow stroke will give an off-beat, driving pulse. This accent pattern can also be used for slurs connecting two notes, especially when the second note is on the first beat of a measure.

"Basic Bowing: The idea is to slur into the beat. The most basic form consists of two notes per bow with the beat falling on the second note. De-DOM where DOM is the beat. This gives a much subtler emphasis than using a new bow for each beat. You have to compensate for the resulting lack of emphasis by using increased bow speed/pressure to emphasize the beat. Using increased bow speed/pressure in the middle of the bow gives a De-DOM sound, or a WAAAH in the middle of the bow." — Joe Carr

Hornpipes

I think of them as slower, syncopated reels. The syncopation will often not be marked on the music; if the name includes the word HORNPIPE, that is a pretty good clue! The jaunty swing that is the mark of a hornpipe has a strong emphasis on the 1st and 3rd beat, with the even-numbered beats often slurring into the odd ones. To provide the syncopation, a sequence that looks like 4 eighth notes will actually be played as a dotted eighth, a sixteenth, dotted eighth, a sixteenth. Ornamental touches will include replacing a quarter notes with a triplet, especially when leading up to a new phrase (or a repeat of one)."We have seen earlier that the note-values, as written, should not be considered exact, but rather as an indication of the melody line. In that respect, the horpipe is no different. Even though a dotted rhythm is shown, the note values, as played, lie somewhere between this and even quavers; the rhythm is dotted, but not to the extend indicated by the notation." —Matt Cranich

- McDermott's Hornpipe, Michael Coleman.

- Rights of Man, a teaching video by Katie Henderson.

Jigs

Wherever jigs originally developed, they are probably the form of Irish folk music that is perceived as most Irish.The time signatures and the triplets on printed music will be confusing to classical musicians. 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8 are actually felt as 2 pulses, 3 pulses and 4 pulses per measure, with an emphasis and a SLIGHT lengthening on the first note of each pulse. Those triplet-looking notations, and variations thereof, comprise one pulse. Newcomers to the world of playing jigs may start out by counting 1-2-3-4-5-6, but the more experienced players will be playing internally to 1-2, 1-2, which aids in getting the pulse right.

Jigs are dance music, but that does not mean that you should start each measure with a strong downbow. Add a bit of subtlety by occasionally slurring from the end of a measure (the 3rd note in the last pulse) to the beginning of the next measure (1st note in the next measure). You can also do this as a transition from one pulse to another; first measure to second, second to third (slip jig); third to fourth measure (slide). Make the slur stronger as you slur into the second note in the slur. This will maintain the emphasis on the most important beat while adding a bit of kenetic energy with the slurring. Observe the video below. Bowing is an important part of the Irish improvisational tradition; Mr Hayes switches up his bowing as he moves from one intensity to another.

- Breanndan O Beaghlaoic, Tommy Peoples, Laoise Kelly on RTRadio 1, John Murray Show. A wonderful example of the ceili band style.

Double Jigs

Double Jigs are the most common form of jigs known to American musicians. They are marked with a 6/8 time signature, which is felt (and performed) as two beats- Michael Coleman, Monaghan Jig, YouTube. A recording of the Sligo-style fiddler who was a recording star in the early 20th century.

- Martin Hayes & Dennis Cahill, Sean Ryan's Jig. Youtube. Martin Hayes is a contemporary Clare fiddle player like no other. One of his trademarks is his ability to take a fast jig and slow it down so that every note and ornament resonates. Dennis Cahill's skill as an accompanist also shines here.

Single Jigs

Marked as 6/8 time, like a jig, but with measures composed of two groups of two notes, a quarter note followed by an eighth note, with the occasional variation.Slides

12/8, felt as four beats. More melodic than jig jigs and, since there are four beats in the measure, twice as long.Slip Jigs

9/8 time, which is felt as 3 beats. Three is an odd number, an asymmetric number, which lends life and lift.Martin Hayes and Dennis Cahill, The Night Poor Larry was Stretched, Slip jig starting at 1:12.

Polkas

2/4, but almost completely unlike a Polish Polka by an accordion orchestra.

Kevin Burke's suggested bowing for the opening measure of Cuz Teahan's Polka had us start up bow and then crescendo from the start to the end of the slurs. Gave it a lot of swing!

Reels

A fast dance in 4/4 time (or, less common, 2/4 time). However notated, you will feel two pulses per measure, not four. The beats are even (not syncopated) unless the syncopation is part of the ornamentation. It may or may not have originated in Scotland, but the history of the reel in Ireland begins about the time it became a big fad in Scotland.The defacto bowing for a fast dance reel is downbow on the first beat. However, Kevin Burke has a very effective alternate bowing pattern that he uses, one which maintains some emphasis on the first beat of the measure but which provides a kinetic kick. If you break the measure down into eight eighth notes (which accomodates the dotted quarter notes frequently found in reels), your bowing goes: Upbow on the first three eighths, downbow on the next three eighths, and then one bow for each remaining eighth.

- Kevin Burke, Boys of Bluehill tutorial.

- Michael Coleman, The Morning Dew, YouTube.

- Martin Hayes, Clonagroe Reel and West Clare Reel.

Waltzes

Until proven otherwise, I consider the waltz to be a transplant. A popular transplant, though. Some of OCarolan's 3/4 pieces make good waltzes and a nice end for a session or a gig.Lilting

AKA as Mouth Music, because it is sung, not played. Technically, one could categorize lilting as dance music, since it seems to have functioned as such during times of extreme poverty and no instruments, but it is such a distinctive art form that it gets its own section.- Comhaltas Live music programs that include lilting.

- Rhiannon Gibbons starts out slow and traditional and ends up... well... rock and roll?

- Joe Harris, All-Ireland Lilting champion, 1975.

- Dolores Keane and John Faulkner, Dance to your Shadow. The syllables and the harmony make it into a compelling performance.

- Rafferty Brothers, mighty lads both, lilt on an RTE TV show, 1982.

- Seamus Brogram lilts Mason Apron, 2007.

Sean-Nós Songs

"[Sean-Nós] does not necessarily refer to any musical terminology but to a way of life as experienced by our people who witnessed many forced changes to the old ways. It is a rather vague way of describing their daily routine at work and play. Songs were made to accompany the work inside and outside the home, to express the many emotions-love and sadness of daily existence, to record local and other historical events and to often mark the loss of family and friends whether by death or by emigration...The first obvious thing to notice abour Sean-nos singing is that it is unaccompanied and performed as a solo art. The singer tells the story in the song by combining many vocal techniques, especially through the use of ornamentation and variation, in linking the melody to the text. Sean-nos singers use different techniques to ornament the performance of a song, One syllable in a word can be sung to several notes and the notes can be varies from verse to verse." —Tomás Ó MaoldomhnaighThis list of the features of Sean Nós are from the Leaving Cert Music website.

- Ornamentation. Sean nós singers use ornamentation to to express emotion. Ornamentation is usually improvised, therefore a song would never be performed the same way twice. Ornamentation can be melodic or rhythmic.

- Free rhythm/metre.

- Solo singing (unaccompanied).

- Variation. The tune and rhythm of songs are varied from verse to verse and from performance to performance.

- Personal styles. Singers often develop their own style of performance.

- Regional Styles. In the past, singers would learn to sing by listeneing to other singers in their region. This gave rise to regional styles of singing much the same as accents in language. The regions are; Connemara, (highly ornamental) West Cork/Kerrry, (nasalisation and glottal stop) West Waterford, and Donegal (simpler more melodic style).

- No Dynamics.

- Little or no vibrato.

Airs

Airs are the opposite of dance tunes; they are often meditative and have a rhythmn that ebbs and flows with the performer's interpretation. Many Sean-Nós tunes are airs, but airs are often performed by one or more instruments.Airs are often written out as 3/4 time, but they are not really waltzes; if the beat is consistent, it is often soft and the beats are not compatible with waltzing.

- Tommy Walsh and Turlough perform Inisheer, Mr Walsh's extremely popular air as performed by himself and his band Turlough. This recording features lyrics at the end.

- Inis Oirr lyrics on SOngsInIrish.com.

TIMELINE

1700

- 1720

- First evidence of baroque violin import into Ireland.

- Late 1700s:

- Fiddle assumes ascendency over the harp, pipes and flute in the playing of Irish folk music, reinforced by the popularity of the fiddle in Scotland and an explosion of reel composition there, which migrated over the Irish Sea to Northern Ireland.

1800

- 1845-49

- Irish Potato Famine of 1845-49. A large proportion of the emigres flee to the US.

1900

- 1903

- Chicago Police Chief Francis O'Neill publishes his first collection of Irish tunes, The Music Of Ireland, in collaboration with violinist and transcriber James O'Neill.

- 1907

- O'Neill publishes his second collection of Irish tunes, Dance Music of Ireland.

- 1920

- Irish music begins to appear on music recordings.

- 1934

- Michael Coleman records "perhaps the most influential single recording in the history of Irish traditional music ... renowned Sligo fiddle player Michael Coleman's recording of the three reels Tarbolton, The Longford Collector, and The Sailor's Bonnet for Decca Records in 1934." — Martin Dowling.

- 1963

- Brendan Breathnach publishes his first collection of traditional Irish tunes. Five of them were published over all, two of them after his death in 1985.

"In an essay on 'The Development of Traditional Irish Music', O'Neill, perhaps stung by a criticism that some of his transcriptions were inaccurate or inauthentic, presented previously published versions of the same tunes, demonstrating how over the years a single tune could be given two different titles, or could change from a jig to a reel, or a reel to a hornpipe." — Chris Haigh.

"The music needs intimacy; it needs to be on a very small, local kind of a scale. You can show off, you can perform, but the real value of Irish music is the transforming property at a local level, like in Connemara when somebody sings a sean nos song to a very small group of people. That, I feel, is the role of folk music, and trying to pull that folk music onto a concert stage that was made for classical music or jazz changes the fundamental aim of your music... What I see the traditional role of music in Ireland to be is this: at the time before television and radio it was the sole means of transporting people out of everyday life...They'd get lost in the music: it would whirl them up." — Caoimhin O Raghaillagh

"There is no one known way of singing it, since what you knew before will not be what you know tomorrow."— Ciaron Carson, as quoted by Mark Slobin.

"[Putting] ornamentations into a song is like when you're courting a girl with your two arms around her. You're not going to do it the other fellow's way. You got to do it your own way."— Joe Heaney, as quoted by Mark Slobin.

Irish Fiddle sheet music online

- Bill Black, Irish Traditional Tune Archive. I estimate that the number of songs on this site is in the thousands, and he updates frequently.

- Hamilton, Hamilton's Universal Tunebook, Vol 1 is chock-a-block full of old music.

- Irish Music Forever: Music, lyrics, chords for a number of Irish ballads at IrishMusicForever.com

- IrishSession.net: Slow Session Sheet Music Booklet.

- PW Joyce, Old Irish Folk Music and Songs, 1909, as PDF or Scorch files.

- Francis O'Neill, Music of Ireland, 1903.

- Francis O'Neill, Dance Music of Ireland, 1907.

- Francis O'Neill, Waifs and Strays of Celtic Music, 1922.

Irish Fiddle tune videos

Toss the Feathers

- The Zorns do an Irish version, fiddle tuned DDAD.

REFERENCES

Dan Accardi, Irish Fiddling, Fiddler Magazine, 2016.

Kevin Burke:

- Irish Bowing Technique, Youtube, 2015.

- The Bowed Triplet, Youtube, 2015.

Joe Carr, A Lesson in Traditional Irish Fiddle Bowing, Fiddle.com, Web.

Saileog Ni Cheannabhain

- A song and interview with a famous young Sean Nós singer and instrumentalist.

Mick Connelly,Fiddle Ornamentation, MickConneely.com, Web.

Peter Cooper, Mel Bay's Complete Irish Fiddle Player, Mel Bay Publications, 1995.

Green Linnet Records has a stellar source for Celtic music for forty years.

Cranich, Matt: The Irish Fiddle Book, Ossian Publications.

Martin Dowling, Traditional Music and Irish Society: Historical Perspectives, 2016, Routledge, New York NY.

Maura Enright:

- Musical Architectures: Modes, Intervals, and Scales. BabaYagaMusic.com.

- Become a Better Fiddle Player, BabaYagaMusic.com.

Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis), The Topography of Ireland, Yorku.ca, Web.

Nick Guida, The Balladeers.com, a wonderful effort at presenting the biographies and the individual albums of Irish folk artists. Some English, Scottish, Welsh, and American folk singers are also included on this web site.

Chris Haigh

- The Fiddle Handbook, Backbeat Books, 2009, Wisconsin.

- Irish Fiddle, FiddlingAround.co.uk, Web.

Joe Heaney, aka Joe Einniu. A biographical movie, Song of Granite, was issued in 2017.

- The Rocks of Bawn, with English words.

Katie Henderson, How to Play a Roll, You Tube video. She is playing slow so the notes on the ornaments sound out.

Tricia Hutton, on the now-defunct KilkennyTradTrail.net.

Leaving Cert Music

Caoimhin Mac Aoidh, Origins of Irish Traditional Music, StandingStones.com.

Donal O'Connor, Ireland's Music Collectors, Web, Comhaltas.ie.

Tomás Ó Maoldomhnaigh

- Amhranaiocht ar an Sean-nos, Comhaltas, Spring 2004.

Mark Slobin, Folk Music, 2011, Oxford University Press.

Irish Modes and Key Signatures at SlowPlayers.org.

Brendan Taaffe, Caomimhin O Raghallaigh: Irish Music at a Local Level, Web, Fiddle.com.

Origins of the Bagpipes in Ireland, NaFiannaPipeBand.com, Web.

Irish Music on Google+

Irish music and Anime on blog.AnimeInstrumentality.net.

Irish Traditional Music Archive (Taisce Cheol Duchais Eireann): Every two months new material is added to the ITMA Online Collections, and it makes for a fascinating read. And then, of course, the music scores offer new insights into old favorites... or is it old insights into newly-discovered favorites...

Dictates Against Harpers, WireStrungHarp.com.

Online Academy of Irish Music has some sample lessons that are useful.

Traditional Tune Archive of N American, British and Irish tunes, formerly known as The Fiddler's Companion.