Meditation and Entertainment

The original Whirling Dervish dance was - and is - a dance meditation, with an hypnotic power over even the uninitated observer. In addition, the whirling dance has long been adapted for entertainment as well, with the performers using multicolored, multilayered skirts that are manipulated to create optical illusions rather than spiritual enlightment.The whirling dance performed for entertainment is called TANOURA. It evolved from the dance meditation that migrated to Eygpt with the Sufi Almoez Ledun Ellah Alfatime. Theatrical versions of the Sufi dance began to appear in Egypt in the late 19th century. The best dancers use more than one skirt, separating and combining them while twirling for hypnotic optical illusions.

While a tanoura dancer whirls, s/he may play large sagat (TOURA) or a frame drum.

- Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, writing in 1718

- William Alexander, writing in 1802

- William Prime, writing in 1857

- Paul Horton, writing in 1977

- Aleta, writing in 2006

- Laurel Gray, writing in 2008

- Mohamed Shahin

- References and Videos

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, in a letter written from Turkey to Lady Bristol in 1718:

"They meet together in a large hall, where they all stand, with their eyes fixed on the ground and their arms across, while the imam or preacher reads part of the Alcoran from a pulpit placed in the midst; and when he has done, eight or ten of them make a melancholy consort with their pipes, which are no unmusical instruments. Then he reads again and makes a short exposition on what he has read, after which they sing and play till their superior (the only one of them dressed in green) rises and begins a sort of solemn dance. They all stand about him in a regular figure, and while some play the others tie their robe, which is very wide, fast round their waists and begin to turn around with an amazing swiftness and yet with great regard to the music, moving slower or faster as the tune is played. This lasts above an hour without any of them showing the least appearance of giddiness, which is not to be wondered at when it is considered they are all used to it from infancy, most of them devoted to this way of life from their birth, and sons of dervishes. ... At the end of the ceremony they shout out; 'there is no god but God, and Mohammed is his prophet,' after which they kiss the superior's hand and retire. The whole is performed with the most solemn gravity. Nothing can be more austere than the form of these people. They never raise their eyes and seem devoted to contemplation, and as ridiculous as this is in description there is something touching in the air of submission and mortification they assume. "

William Alexander's description of the Mewlewys Dervises in 1814:

"The Dervises... are divided into thirty-two sects; and there is not perhaps one of them, of which the regulations or practices are more curious than those of the sect of Mewlewys, of which Djelal-ud-dinn Mewlana was the founder. This sect is particularly distinguished by the singularity of their mode of dancing, which has nothing in common with the other societies. These dervises also have peculiar prayers and practices. When they perform their exercises in public is is generally in parties of nine, eleven, or thirteen persons. They first form a circle, and sing the first chapter of the Koran. The Chief, or Scheik, then recites two prayers, which are immediately succeeded by the dance of the dervises. They all leave their places and range themselves on the left of the superior, and advance towards him very slowly. When the first Dervise comes opposite the Scheik he makes a salutation and, passing on, begins the dance. It consists of turning rapidly round upon the right foot with the arms widely extended."

William Prime's description of the dance of the 'derweeshes' in 1857:

"...a man dressed in a long white hooped dress, tight at the waist and some twenty feet in circumference at the bottom of the skirt, slid into the centre of the half circle, and commenced a slow revolution, apparently as gentle and easy as if he stood on a wheel turned by machinery. After a minute, during which he swung out his skirts and started fairly, his speed increased. His hands were first on his breast, then one on each side of his head; and when the full speed was attained, they were stretched out horizontally, the right hand on his right side, with the palm turned up, and the left hand on its side, with the palm down. For twenty-four minutes, without pause, rest or change of speed, he continued to whirl around like a top. The velocity was exactly fifty-five revolutions to the minute. I timed it frequently, and was astonished at the regularity. This was not a long performance. It is oftentimes an hour, and even two or three hours, in duration."

Paul Horton writing in Saudi Aramco World in 1977:

"As in medieval Europe, where the first geared clocks are believed to have appeared in monasteries to help regulate the daily prayer services, so in Istanbul the first Turkish clocks were made in the tekkes, or monasteries, of the so-called "Turkish monks," the Mevlevi Dervishes, better known to Westerners as the "Whirling Dervishes." The Mevlevis were considered the most intellectual of the Dervish orders and were well known for their interest in music and the arts. They acquired an interest in making mechanical clocks, their elders now suggest, to help initiates of the order observe fixed prayer times during long periods of meditation. More reliable than sundials and not requiring as much attention as a waterclock, the clocks also provided a focus for the communal life of the monastery."

"Many of these timepieces . . . were presented to the Sultan by the Mevlevis as a sign of their loyalty. A 16th-century illuminated manuscript shows a procession of different artisans before Sultan Murad III, and an account of their visit in a royal diary mentions among those who presented themselves to the Sultan the "magic" Mevlevi clockmakers. As the assembled audience watched in amazement, the diary tells us, they entered the hall with an oversize model of a clock gearwork mounted on a wagon. A hammer automatically struck the gearwheel, turning a second wheel which, the chronicler observes, "could perform the work of a dozen persons." The Sultan and his audience burst into applause and cheered the clockmakers as they pulled their display away."

Aleta, writing in 2006:

"There seems to be a dearth of information about the history of the tannoura. The most obvious idea is that Mevlevi Sufis travelled to Egypt and practiced the whirling Sema there. The Egyptians picked up the practice both for devotional purposes, as practiced by real the darawish (from dervish), and as a folk dance. The tannoura evolved to include the bright skirts, specific movements and music, folkloric introductions, and so on.

"However, dance researcher Laurel Victoria Gray writes of a different possibility. She studied tannoura with Adil, the sagat player and leader of the group dancers [The Al Tannoura Troupe] as mentioned above. She writes: 'But then Adil told me that tanoura had been introduced to Egypt by the Fatimids.'

"The Fatimids captured (and named) Cairo around 970 CE, invading from Tunisia (although Said ibn Husayn - the founder of the Fatimid dynasty - was Syrian, he travelled to Tunisia and founded the Caliphate there). The Seljuks captured Cairo in the mid 1100s, so the introduction of tannoura would have been between 970 and 1100 CE. The Mevlevi order of Sufism was founded in 1273 CE by followers of Jalal al-Din Muhammed Rumi. Consequently, if the tannoura was brought to Egypt by the Fatimids, its origin predates the Mevlevi.

"The practice of spinning is quite ancient and occurs in many cultures. Spinning was practiced in Iran, Rumi's original home, long before Rumi's followers founded the Mevlevi order. Sufism is as old as Islam in the broad sense of mystic practice (7th century CE), with formal theorists first occurring around the 9th century. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that both the Mevlevi Sama and the Tannoura derive from a single, preexisting tradition."

Laurel Gray, writing in 2008:

"It seemed odd that I would be so frantic to get in. I had seen many performances of tanoura (the Egyptian whirling dervish dance) on video and always considered it to be a theatricalized, circus version of the elegant ritual of the Turkish Sufis. The brightly colored skirts, often twirled off of the waist and above the dancer's head, seemed to me to be an example of airport art — traditional folklore twisted into a consumer product for tourists.

"Yes, the Turkish sema, as the turning ritual is properly called, is quite different from the Egyptian tanoura. Years ago, in graduate school, my Turkish friends asked me to organize publicity for a Turkish Festival at the University of Washington. They had arranged an exciting and multifaceted event featuring music, dance, crafts and art. But the highlight was to be an appearance by a whirling dervish group based in Canada, which would present a formal sema.

"I was transfixed. The unrestrained, folkloric purity of the music intoxicated. A group of men, dressed in long white galabiyas, moved in unison to the rhythms. At times they moved forward and back in a line, like waves crashing against the shore. Sometimes they traveled in a circle, all the time accompanying themselves on the riq, or tambourine. My eyes were repeatedly drawn to a tall man playing a pair of sagat the size of saucers. He used the finger cymbals to create intricate syncopations against the driving, dominant rhythms while striking elegant postures that were oddly familiar. Sometimes, he balanced on one leg, crossing the other foot in front. His posture and control were perfect.

"During the evening, two different soloists presented the tanoura, and while their exuberant energy was a complete contrast from the contained solemnity of the Turkish sema, Spirit was present here as well. When the performance finally ended, every person in the room was enraptured."

Mohamed Shahin: Whirling dervish, or 'raqis tanoura' in Arabic (literally translated as 'skirt dance') is the traditional dance of the Sufis, and has its origins in the Turkish Ottoman Empire. It started as an alternative form of worship within Islam, and is performed as a way of inducing an intense personal communion with the divine, of inducing ecstasy. Sufi practitioners of the dance wear long white kaftans, fez-like hats, and a heavy white skirt traditionally made of wool, in which they spin for hours around a fixed imaginary point. With his circular motion and accompanying hand gestures, the Sufi dancer engages in a sort of physical prayer, whereby he emits a huge bout of energy to the heavens. Tanoura dancing is usually done in groups, with one man in the middle whirling, while the other practitioners dance around him in a circle. It is as if the dervish were the sun, and the dancers revolving around him, the stars.

The Egyptian tanoura dance is similar to the one practiced in Turkey in all but dress. Primarily performed for theatrical rather than spiritual reasons, Egyptian dervishes wear ornate and colorful skirts and incorporate the use of accessories to demonstrate the difficulty of the dance and the dancer's skill.

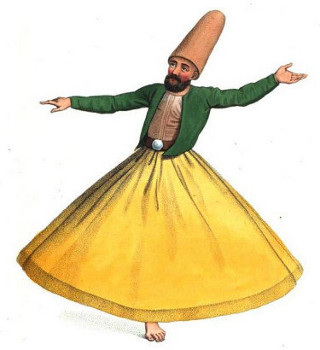

A Turkish Dervise by Octavian Dalvimart, early 19th century

REFERENCES

- William Alexander, Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Turks, London, 814. .

- Liliana, The Art of Tanoura, Bellydancemag.com.

- William Prime, Boat Life in Egypt and Nubia, a travelogue published in 1857.

- Joe Williams, Delsarte teacher and dancer based in NYC, in his Whirling Dervish personna.

- Mevlana.net is maintained by descendents of Rumi (Mevlana).

- Sema Ceremony in Istanbul.

- American whirling dervishes, male and female. Very short, but informative.

- Theatrical whirling dance with multi-layer skirt in Cairo, Egypt.