- Who ARE the Ghawazee?

- Characteristics of Ghawazee Dance

- European Explorers and Artists meet the Ghawazee

- America Encounters the Ghawazee

- Ghawazee Costume

- Ghawazee Music

- References

Who are the Ghawazee?

The Egyptian Ghawazee are the decendents of nomads who migrated from India through the countries of the Far and Middle East and then down into Egypt, probably in the 16th century. Their traditional occupations in Egyptian communitites are as dancers, singers and musicians for social events large and small.

Their non-Egyptian and non-Arab origin, distinct from the culture around them, and their traditional occupation as entertainers has been asserted by both historians and themselves for centuries.

The early 19th century orientalist Edward Lane described them as "a distinct race...[who] sometimes make use of a number of words peculiar to themselves."

Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911 edition: "The Ghawzi (sing. Ghzia) form a separate class, very similar to the gipsies. They intermarry among themselves only, and their women are professional dancers... They dance in public, at fairs and religious festivals, and at private festivities, but, it is said, not in respectable houses. Mehmet Au banished them to Esna, in Upper Egypt; and the few that remained in Cairo called themselves Awalim, to avoid punishment. Many of the dancing-girls of Cairo to-day are neither Awlim nor Ghawazi, but women of the very lowest class whose performances are both ungraceful and indecent."

Edwina Nearing, describing her field research in the late twentieth century, wrote: "My own research among the Awlad Mazin of Luxor, a family which for many years have provided the leading ghawazi of Egypt, confirmed. . .that the ghawazi comprise at least several obscure ethnic groups. . . Each group, apparently, has its own language; the Mazins, who are of the Nawar, claim that their language is unrelated to any of those spoken by the other groups. The small Nawari vocabulary I have collected demonstrates some affinities with Hindi, suggesting that the Nawar may have originated in or near India, probably in or near North India, if more circumstantial evidence I have uncovered is valid."

Ibrahim Farrah, in his interview with Alan Weber: "While playing at celebrations in Upper Egypt in those early days of his rabab career (1975), he [Alain Weber] would often see the ghawazee. Joseph (Yusul) Maazin, patriarch of the clan of daughters who became the most familiar ghawazee dancers of contemporary times, was still alive and Mr. Weber maintained contact with him and his dancing daughters... Weber maintains that the Banaat Maazin are the descendants of the ghawazee as described by the latter nineteenth century European travelers. They inhabit the same regions of Esna, Aena, Luxor and Balyana. They come from the same tribe of Nawar which is believed (by many) to have migrated from Persia. The home language of these Nawar is Farsi, of which some of the ghawazee and the Manaat Maazin still speak a little among themselves. Mr Weber said that although the daughers spoke little Farsi, Joseph Maazin still knew 300 to 400 words, and that this Farsi vocabulary is what is meant by the 'secret language of the ghawazee.'"

Yousef Maazin, as interviewed by Jeremy Warre: "Our tribe originally came from Kurdistan, many generations ago, having been cast out of our homelands because of our evil deeds and bad reputation. For in truth we would steal and plunder and some of us were highway robbers too. We lived outside society and we kept alive our own traditions and our own language. But we were punished and driven out of Kurdistan and Iran where our forefathers were born. In the beginning we took after our ancestors, but we had to pay for that, for the people were against us. In order to settle in Luxor, we encouraged our daughters to dance and our sons become musicians so that we would become accepted by the locals. And we invaded their hearts and their minds by our arts."

For centuries the Ghawazee have thrived as entertainers and sex workers, but the increasingly conservative Muslim culture in Egypt in the late 20th and early 21st century, coupled with the newer generation's obsession with Western culture, has destroyed their customer base. The Benat Maazin family were the last to perform publicly in Egypt. Khairiyya, the only one of the Maazin sisters who has not retired, occasionally finds work in Egypt and overseas teaching the Ghawazee dance to enthusiastic Western students. In short, in the forty years since American dancers 'discovered' the Benat Maazin, the Ghawazee have gone from prosperity to near extinction.

"Ghawazi used to be a very important part of every festive occasion; weddings, engagement and circumcision parties, moulids. Often, women would hire female entertainers or men just partying with the men would hire professional musicians and female entertainers. Those Ghawazi dancers and musicians were working 24/7 most of the year... Now they are starving because of the changing religious and social climate... In upper Egypt the Ghawazi recently had to 'retire' because fundamentalists threatened to disrupt any local wedding or party hiring female performers. The few Ghawazi left in Luxor make what meager living they can by teaching their dances to Foreigners who come to learn or from performing at rare private parties for those foreigners who know where and how to contact them."— Morocco

Characteristics of Ghawazee Dance

"Commonalities in movement are huge hip swings, hip shimmies layered over other hip movements, shoulder shimmies, spins and foot stomps to emphasize accents in the music, occasional head slides, back bends and some floor work. Ghawazee music is organic in sound, utilizing instruments like the mizmar and rebab with tabla, tar, and finger cymbals for percussion."— Salome

"Their slow movements in the dance, accompanied by sighing rababas, has the mesmerizing, self-absorbed languor of an odalisque, slowed down Time itself. Their fast work was infused with such energy that the dancers seemed to vibrate, and they played off of each other— unconsciously took cues from each other's movements as they improvised, and meshed accordingly— such that at times it seemed there was an electrical current between them, a marvelous tension that ensnared the onlooker."— Edwina Nearing

"The Ghawazee dancers of Egypt were a nomadic gypsy tribe who eventually settled there, despite discrimination from the Egyptian villagers. The lively dance of the Ghawazee later became a primary source of inspiration for indigenous Egyptian dance. Their style consists of simple, repetitive hip lifts, turns and constant playing of finger cymbals. Like most Middle Eastern tribal and trance styles of dance, the Ghawazee rhythms progressively get faster with the finale building to a frenzied and ecstatic shaking of the hips."— Keti Sharif

European Explorers and Artists Meet the Ghawazee

Edward Lane, 1860:

"EGYPT has long been celebrated for its public dancing-girls; the most famous of whom are of a distinct tribe, called Ghawazee. A female of this tribe is called Gázeeyeh; and a man, Gházee; but the plural Ghawázee is generally understood as applying to the females. The error into which most travelers in Egypt have fallen, of confounding the common dancing-girls of this country with the A'l'mehs, who are female singers, has already been exposed. The Ghawázee perform, unveiled, in the public streets, even to amuse the rabble. Their dancing has little of elegance. They commence with a degree of decorum; but soon, by more animated looks, by a more rapid collision of their castanets of brass, and by increased energy in every motion, they exhibit a spectacle exactly agreeing with the descriptions which Martial and Juvenal have given of the performances of the female dancers of Gades.... In general, they are accompanied by musicians (mostly of the same tribe), whose instruments are the kemengeh, or the rabab, and the tar; or the darabukkeh and zummarah or the zemr: the tar is usually in the hands of an old woman."William Prime, 1860:

"The two girls who came down to the boat were fair specimens of the class; one of them held a species of banjo or guitar in her lap, on which she beat a sort of tune, while the other danced slowly, and with some degree of skill, to the measure. Their taste in dress was far above the ordinary run of women in Egypt; for the natives of the lower classes, as I have already stated, wear but a single long, loose garment, while these girls were loaded with the usual full dress of the lady of the hareem."Alain Weber, late 20th Century:

Alain Weber is a French music impresario and ethno-musicologist who was introduced to Egyptian folk music during a tour he organized for the National Folk Troupe of Egypt. He ended up moving to Egypt and organizing the touring musical group The Musicians of the Nile, comprised of native Egyptian musicians and himself, on rabab."In the initial years of producing these musical tours of Europe, Mr Weber felt that a 'typical' dancer would be an added charm to the program. However, it appeared that European critics could not find equal appreciation between the sight and the sounds. We all too fully know the power of the press, so these negatve reviews and criticisms about the use of the ghawazee dancer in his program encouraged Mr. Weber to eliminate this aspect of his concerts. He came to believe that the French public did not feel that the fifteen-minute dance portion of the show attained the same level of quality as did the musical portions. Perhaps the public's disappointment may actually have laid in greater expectations for a more elaborate or more showy oriental cabaret style... Arabesque thinks too that the accommodating press with their intriguing reports on the ghawazee with their Gypsy heritage who remained attached to their traditions [led the] European public to believe they would be experiencing something akin to flamenco in passion and technical complexity."— Ibrahim Farrah

Jeremy Marre, late 20th Century:

Jeremy Marre's 1992 video, "Gypsy Music into Africa," includes two interviews with members of the Maazin family in Luxor, Egypt. A performance by three of the Maazin sisters singing and dancing to live music is included.Su'ad Maazin: "The only time I wish I was not a dancer is when a man of another tribe falls in love with me or one of my sisters. His family would fight a war to stop him marrying a girl of bad reputation. His family would say, How can you do such a thing to us? How could you marry a daughter of Maazin, a dancer and a singer, a girl who performs in front of others? Then such a marriage becomes impossible... We don't care what they say because at the end of the day we give them their money's worth and they get what they are after."

America Encounters the Ghawazee

The 1893 World's Columbian Exposition included a Midway of entertainments, among which were concessions exhibiting Middle-Eastern and African dance. Thanks to Sol Bloom's decision to use the French term danse du ventre (dance of the belly) to describe some of the entertainment at his Algerian Village, Middle Eastern dances that had been quietly introduced at other venues in the 19th century became the subject of scandal and uproar, which was in turn quickly capitalized on to sell dance performances, music and even books with a "Ghawazee" theme.

Several months after the Chicago fair closed, several of the exhibits, including A Street in Cairo, moved to the Grand Central Palace. The dancers included 3 Algerian and one Egyptian dancer. Since the NYC police were then under close public scrutiny for connections with organized crime, Inspector Williams decided that a crackdown on the danse-du-ventre would be the perfect distraction. A series of really, really, REALLY hilarious newspaper reports ensued during the NYC prosecution of four Cairo Street dancers for immodesty.

Aisha Ali, late 20th century:

Aisha Ali went to Egypt in the early 1970s to study Egyptian folk dance in general and the dances of the Ghawazee in particular.In a series of articles titled Meetings in the Middle East, Aisha Ali recounted her efforts to seek out the Ghawazee "whose life style, costumes, and music were those that had originally excited my interest." It was a long search with a lot of dead ends. When she heard that entertainers similar to the Ghawazee might be found among the Roma of Lebanon, she went to Syria. She discreetly crashed weddings at the Nile Hilton. Yet another excursion ended unpleasantly when a woman objected to having her picture taken... and her relatives picked up stones.

After Aisha was introduced to Mahmoud Reda, he arranged for a famous ghaziyee from Monsura to come to Cairo to visit Aisha. One of the Reda dancers also introduced her to Nezla El Adel, who demonstrated her famous acrobatic splits and shimmies and candelabra dancing. However, none of these dancers were the Ghawazee she was looking for.

During her second trip to Egypt, in 1973, she decided to go to Upper Egypt to see the Benat Maazin. Reda wrote her a letter of introduction and warned her against involvement with a Mr. Khalil, a well-known agent for the dancers and musicians in Luxor. In a comic mix-up at the Luxor airport, Aisha ended up being transported to Mr Khalil and giving the letter of introduction to him. He immediately accompanied her to the village where the Benat Maazin lived. When patriarch Yousef Maazin informed them that his daughters were scheduled to dance that evening on an excursion boat, Khalil suggested that Aisha also go as a performer, gave her advice on what to wear and how to conduct herself, and send an escort at sunset to bring her to the boat. When the dancers unwrapped themselves to perform, Aisha saw the crescent-shaped headdress, knee-length skirts and narrow panels of the Ghawazee she had been looking for.

"Their dance music was wonderfully familiar to me, as I had been dancing to the Koizumi and Hickmann recordings for many years, and although their style was different from anything I had seen, I was able to imitate them at once, being accustomed to the technique required for their walking, vibrating shimmies. When I had danced for a short time, the three girls came out to join me and two of them dipped into a back-bend, supporting each other by pressing the backs of their heads together, while the third did the same thing with me. From this position, I was surprised by one of the girls breaking away suddenly and bending back further until her face was below mine. At this point she kissed me on the lips. I later learned that this was part of an old tradition among the Ghawazee."

Khalil gave Aisha several interviews about the history of the Luxor Ghawazee and arranged a party with the finest folk musicians and singers where Aisha was able to tape the music to her heart's content. His generosity provided her with the information she needed to reconstruct a Ghawazee dance in the style of the Benat Maazin for her own dance company's performance in London in 1974, where the lead Egyptian musician told her that the Maazin girls were prospering and enjoying a much broader recognition, thanks to the Egyptian Ministry of Culture's decision to bring them to Cairo for a television special.

At the end of 1974 she returned to Egypt and danced with Maazin at parties and festivals, becoming more acquainted with their personal and professional lives. She made special note of their professional demeanor when offstage. It also was a performance calculated to please. "There was a contingent of handsome young men from the nearby village who had been hanging around all evening hoping for an opportunity to speak with one of the Maazin girls, and I was charmed by the special style of coquetry that the girls used on these hopeful youths. Their manners were at once girlish and queenly, innocent and wise, and they became vulnerable when it suited them, but were always aware of the power they commanded over men." She also noted that after Khalil asked her to perform 'oriental dance' at a party where the primary entertainment was the Maazin sisters, the enthusiastic response of the audience inspired Khaririyeh Maazin to train her daughter Shadia in raqs sharki as well.

In 1977 Aisha returned to Egypt with her brother with the intention of filming country dances. Khalil offered to allow her to film the entertainers performing in a movie he was making if she would perform at a publicity party. The entertainers at the party included the Benat Maazin sisters and little Shadia, who was now performing raqs sharki. When Aisha went to the Maazin home for dinner, she found that Khairiyeh's decision to debut Shadia as an oriental dancer was not popular with the rest of the family; the Maazins felt that oriental dance cheapened their image as traditional country dancers.

Edwina Nearing, late 20th century

Edwina Nearing is an American dancer and journalist who did field research on the Egyptian Ghawazee in the 1970s and, like Aisha, followed many a crooked lead until she was introduced to the Benat Maazin. Her series of articles, The Mystery of the Ghawazee, was originally published in Habibi magazine. Edwina Nearing included a lot of historical, literary and research material from other authors in her articles, much more so than Aisha, who pretty much restricted herself to what she saw.Edwina has continued to follow the Benat Maazin family up to the present day, through the collapse of the family fortunes and the persecution by radical Islamists. In the article Ghawazi on the Edge of Extinction (published in 1993 in Habibi magazine) Edwina describes the swift and devastating change in opportunities for work that took place between 1992 and 1993:

"I had entertained some thought of working ... with Khairiyya and RajŠ as I had in the past; their sisters had retired, leaving just the youngest two to carry on, and the villagers preferred to hire groups of three or four ghawazi for greater honor and a braver show. . . But Khairiyya had disturbing news. The authorities in Qena, the provincial capital, had outlawed public dance performances in the villages where they were most popular. . . Khairiyya assured me that although she could no longer work at the great farahat parties, opportunities for work within the town of Luxor itself had increased dramatically. Travel agencies, hotel management and restaurateurs had finally awakened to the fact that the hordes of tourists who descended on Luxor during the winter to see the tombs and temples of the pharaohs wanted something to occupy their time in the evenings too, and that there could be profit in it.. . there was enough work in Luxor to keep the ghawazi fully occupied, at least in the winter— dancers were even being brought in from Cairo. So it was that I was able to see several performances by the Banat Mazin during my brief stay in Luxor in 1992, and I had reason to hope that the ghawazi would survive for a while longer.

However, within one year this new prosperity went bust. When Edwina visited the Benat Maazin in January 1993, Khairiyya told her Luxor was now inundated with oriental dancers from Cairo who were willing to exchange sexual favors for work or gifts and to perform in any venue. "She thought they had come down from Cairo from fear of the rhabiyin; I thought it more likely that they were just looking for steady work and had heard of the demand for dancers in Luxor. Whatever the reason, their numbers and easy availability had driven out the true folkloric artists; the local musicians had even turned against the Banat Mazin, Khairiyya said, preferring the more accommodating dancers from Cairo. And the favor of the musicians was important for obtaining work in Luxor, as most employers in the town, often inexperienced in the entertainment business or from outside the area, left it to the musicians to recommend or provide dancers, unlike the Sa'aida of the countryside who knew their dancers and contracted with them directly...now, in January of 1993, there are no ghawazi performing in Luxor."

Habiba, late 20th century

Habiba did dance research with the Maazin family in the mid 1980s and has taught and lectured on Ghawazee dance for years. Like Edwina Nearing, she includes historical, literary and research material from other authors in her articles.Her article Ghawazi Revisited: A Party in Luxor relates her first meeting with the Banat Maazin and includes a charming and detailed description of the party she organized at a Luxor hotel in 1985 with the Maazin sisters and local musicians as the featured entertainment.

"Soon, Fayza and Samia made a dramatic entrance. They were almost completely unrecognizable to the girls I saw that morning. These somewhat arrogant and self-assured creatures made everyone gasp as they swept into the room. Immediately, the excitement level rose. Their persona was completel different from their daytime affect and was probably learned as a family tradition. That morning they had had the air of sulky children, but that evening they were arrogant, worldly, temperamental, unpredicatable and utterly devastating."

Habiba's 2005 article on The Legacy of the Ghawazi includes a detailed history, a description of several of their dances, and an amusing paper-doll-like illustration of herself and her various Ghawazee costume pieces.

Morocco

Morocco, a famous American dancer and researcher of Romany extraction, first encountered the Ghawazi in her trips to Egypt in the 1960s."Yusuf Maazin had five talented daughters. In the 1950s and 60s the three older daughters, Suad, Toukha and Firiual danced together. In the 70s and 80s, it was Khairiyya and Redja, the two younger sisters — the ones in my #6 DVD... The Ghawazi are not Roma, they are Sinti, who were from anouther part of India and arrived in Europe separately from the Roma, but the locals lump them together, so Marre's documentary did too. All real Ghawazi are Sinti, but not all Sinti are Ghawazi... Ghawazi were more respected by their public than Oriental dancers, but not by much. The Banat Maazin were more respected than other Ghawazi, including some in their own family, because of their father's strength and defense of his daughters and their own class and impeccable moral conduct... The Maazin clan was in an uproar in 1978, when Shadiyya Maazin, a cousin, "went Orientale." She got a job in Italy, married the club's owner and retired, so they calmed down."

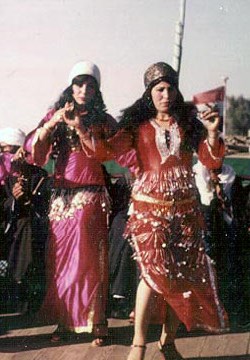

Ghawazee Costume

The Ghawazee costume evolved over time; they were entertainers, not historians, and adapted their dress to maintain their status as entertainers.

"Different regions in Egypt had different extended Ghawazi families doing different dances. Costumes depended on what was in style and available. What some Westerners mistakenly assume to be old style Ghawazi costuming, based on Roberts' and Gerome's 19th Century paintings, was what upper-middle class Ottoman women wore at home but covered up on the street. Dancers wore the same clothing, with scarves around their hips (to show their movements), using the best fabrics possible to show their wealth and status, but this was still everyday clothing... Their [the Maazin sisters] father, aunt and the older Maazin sisters told me that they invented their own elaborate costume as a way of declaring their uniqueness — pure show biz. They made their own skirts: four meters of net fabric, totally hand beaded with several rows of bugle bead fringe and paillettes at the ends, so that the skirt weighed over thirty pounds... The older sisters (before they got married) word long skirts, almost ankle length; by the time Khariiyah and Redja were dancing, the skirts were shorter, because shorter skirts were in fashion and it took forever to bead the longer skirts... Ghawazi in Luxor / Quene / Esna always wore shoes: 1.5" heels or wedgies"— Morocco.

Habiba wrote in 1985 that the Maazin dancers used what she termed the Luxor costume (a baladi dress ornamented with paillettes mounted on long strings of beads) when they danced at hotels, and their Pharonic costumes when dancing at a local event or wedding. "The thing that struck me as most touching was their charming use of quite ordinary junk jewelry from the '50s in their crowns (taj). It was resourceful and imaginative."

Ghawazee Music

- Aisha Ali's famous collection of field recordings, Music of the Ghawazee, is available for download at Amazon.com.

- Edwina Nearing discusses the musical rhythms and the Zill technique used by the Maazin sisters in her article Sirat Al-Ghawazi , originally published in Habibi magazine and now online at GildedSerpent.com

As sketched in 1878 by CB Klunzinger.

References

Aisha Ali, Meetings in the Middle East, Arabesque Magazine, 1979 - 1981, Print.

Aisha Ali in a short clip of Ghawazee style dance, wearing the older style Pharonic dress.

Aisha's famous collection of field recordings, Music of the Ghawazee, is available for download at Amazon.com.

Pepper Alexander, Researching Dance Origins with the Mazin Family, Gilded Serpent.com. Web. Photos from 1979 field work.

Benjamin Aldead, American Bellydance: From Columbian Exhibition to American Tribal Style, University of Chicago Library News, Web.

Maura Enright, Cairo Street Comes to Manhattan, BabaYagaMusic.com, Web.

Maura Enright, Sol Bloom Loved Middle Eastern Dance, BabaYagaMusic.com, Web.

Ibrahim Farrah, From Bon Chic, Bon Genre to Bumming on the Nile, Arabesque Magazine, 1991: a biography of Alan Weber.

Laurel Victoria Gray, of the Silk Road Dance Company, is an accomplished costumier. Here is a short video clip of her Company performing in her theatrical version of the Pharonic costume.

Habiba, Ghawazi Revisited: A Party in Luxor, Arabesque magazine, 1985, print; updated in 2003, web.

Habiba, The Legacy of the Ghawazi, Habibi Magazine, Fall 2005, print; Habibastudio.com, Web.

Habiba, The Ghawazi: Back from the Brink of Extinction (For now), GildedSerpent.com, 2009, web.

Habiba, Legacy of the Ghawazee, 2009, has an amusing paper-doll-like illustration of herself and the Pharonic custume pieces she purchased from the Maazin sisters at the top of her article about the

Craig Harris, Musicians of the Nile, AllMusic.com, Biography and discography. Web.

Edward Lane, Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, 1860.

Maazin sisters: Short excerpt of a 1967 movie that included three Maazin sisters dancing in their distinctive Pharonic costume. Close-ups of the costume, which includes the distinctive panel overskirt and crown, start at second 40.

Khariyya Maazin: 2006 video of Khariyya in Luxor costume with many strings of beads and pailettes attached from bodice to knee.

Kharyia Maazin: 2005 video of a private lesson with Kharyia.

Kharyia Maazin: 2010 brief video of Khariya performing with zills,

Kharyia Maazin: 2010 brief video of Kharyia teaching a dance class while zilling.

Morocco, You Asked Aunt Rocky,Answers and Advice about Raqs Sharqi and Raqs Shaabi.

Edwina Nearing, Ghawazi on the Edge of Extinction, Habibi magazine, 1993: Print and Web.

Edwina Nearing, A Future for the Past: Cairo's New School for Traditional Music and Dance, Habibi Magazine, 1993, print and web.

Edwina Nearing, Index of Nearing's articles on the Banat Maazin Shawazee on Gilded Serpent.com.

Edwina Nearing keeps in touch with Khairiyya; read a few letters at AswanDancers.org.

Nissa, Reconstruction of Egyptian Belly Dance at the Turn of the 19th Century, You Tube clip of a best-guess reconstruction.

PBS, The World's Columbian Exposition (1893), Web.

William Prime, Boat Life in Egypt and Nubia, Harper & Brothers, 1860. Print and Web.

Salome, A Professional Style Terminology, Oriental Dancer.net, Web

Keti Sharif, Bellydance, Allen & Unwin, 2005. Print.

John Harvey Whitson, Chicago Charlie's Diamond Dash, A Story of the White City, 1893, Web. "Where the Ghawazee's heart is, she will-a there go!"

Ghawazee dancers of the mid-19th century, sketched by Edward Lane. This is a standard folkloric costume for dancers today.

Pictures of the Ghawazee dancers at the 1893 Chicago exposition display the panel overskirt and the vest over a long chemise that was part of the Maazin sisters' Pharonic costume in the mid-20th century. The panel overskirt has been revived by some American Tribal dancers for their own performance costumes.

Picture taken in 1979 by Betsy Fishman: Luxor dancers entertaining the passengers on a boat cruise. Note the dress on the dancer in red; pailettes on the ends of long strings of beads give great emphasis to the smooth circular motions of the hips.